The nineties as a decade of change in African and global exploration patterns

Gregor Borg

Institute for Geological Sciences, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Domstr. 5, 06108 Halle, Germany

The last decade and particularly the last five to six years have seen dramatic changes in mineral exploration in Africa in respect of both total activity and areas under exploration. The following article outlines the significant changes that have taken place in the global economic framework of mineral exploration during the last decade with a special emphasis on Africa. These changes might also stimulate the geoscientific community to cooperate even more closely than in the past. Ore deposit research is particularly suited as 'industrial geoscience' or 'near industry research' when it is - at least partly - aimed to improve existing exploration models and thus can assist the international exploration community. Or as the Mining Journal has recently phrased it: 'The skill of geologists in identifying prospective areas for exploration, and then undertaking the detailed search, remains a valuable commodity. It is a skill which must be learnt from study, experience and communication.' (Mining Journal, Exploration Supplement, 1997, p.1). This summary is based on data published by periodicals such as the MINING JOURNAL, MINING ANNUAL REVIEW, THE METALS ECONOMICS GROUP, AFRICAN MINING and various industry sources.

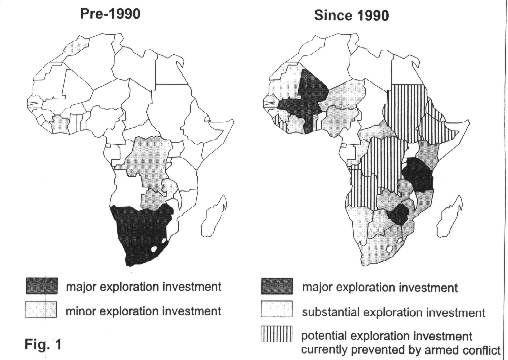

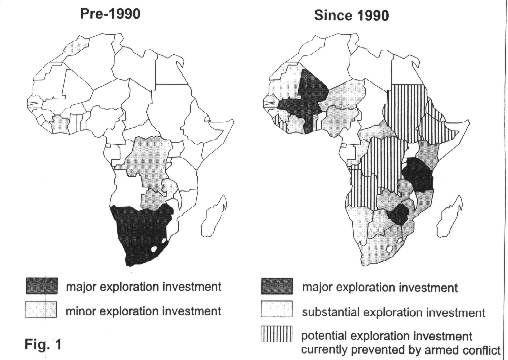

Prior to 1990, Africa attracted relatively little attention from the international exploration community with the southern African Countries, such as South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Botswana being the main focus of exploration at the time. This exploration was carried out predominantly by a few South African mining houses. Limited mining and exploration activity outside these countries was generally restricted to Zambia, Zaire, Ghana and Morocco (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Maps of the geographic distribution of exploration investments in African states pre-1990 (left) and post-1990 (right).

Changing patterns in global exploration expenditure

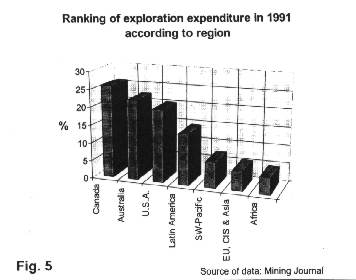

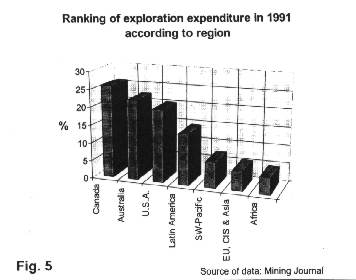

During the last few years, global spending on mineral exploration has tripled from 1,53 billion US $ in 1991 to 4,6 billion US $ in 1997. The African continent attracted not more than 4,7 % of the world's total exploration expenditure at the beginning of this period (Fig. 2). However, since then, Africa's share of the 4,6 billion US $ has risen to 16,5 % or 759 million US $ (Figs. 2 and 3). This change is most dramatically illustrated when comparing the relative increase of exploration expenditure in different regions (Fig. 4). Of all regions, Africa shows by far the most impressive increase of more than 900 % of its 1991 exploration expenditure! This last decade, however, has seen a more complex reshuffling of exploration activities on almost all continents. In 1991 the ranking of exploration expenditure in different regions (Fig. 5) followed a rather stable distribution pattern established several years ago. This patterns saw Canada with 25,8 % followed by Australia (22,3 %), the U.S.A. (20,2 %), Latin America (14,3 %), SW-Pacific region (7,2 %), the European Union (EU) together with the Community of Independent States or former Soviet Union (CIS) plus the rest of Asia (5,5 %), and finally Africa (4,7 %).

Canada had been ranking first in its share of global exploration expenditure for ten years between 1981 to 1991. After that it has lost this position to Australia in 1994 and subsequently to Latin America in 1997.

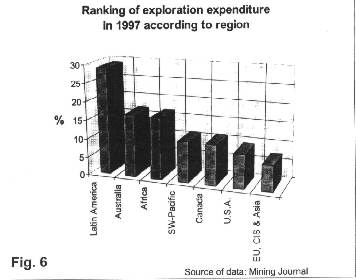

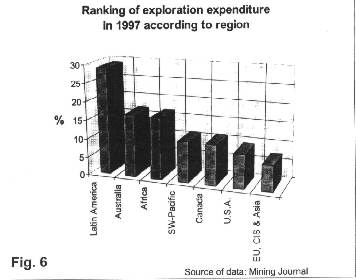

In 1997 Latin America attracted almost every third dollar (29 %) spent world - wide on exploration (Fig. 6) and it is now followed by Australia (16,7 %), Africa (16,5 %), the SW-Pacific region (10,9 %), Canada (10,8 %), U.S.A. (9,1 %), and the EU, CIS and Asia (7 %) now at the end of this list.

This means that expenditure in Latin America has moved to pole position from fourth rank while Africa has left behind its seventh place and moved up to third position. Canada, the U.S.A., the EU, CIS, and Asia languish toward the rear. These modifications have affected virtually all regions although the least changes appear to have occurred within the EU, CIS and Asia. Another statistical diagram can be developed from the data of Figure 2 and might better serve to stress the systematic differences in global exploration patterns. Figure 7 presents the relative change in the percentage of global exploration expenditure within each area between 1991 and 1997. Such an illustration helps to distinguish those countries whose relative share in global expenditure has risen during this period from the ones whose share decreased. 'Losers' in this respect are Canada (- 58 %), the U.S.A (- 55 %), and Australia (- 25 %) where exploration expenditure has decreased relative to world-wide spending increases (+ 301 %). The 'winners' in this competition for funds are Africa (+ 251 %), Latin America (+ 103 %), the SW-Pacific region (+ 51 %) and even the EU, CIS and Asia (+ 27,3 %), areas or continents which have successfully increased their portion of the 'global exploration budget'.

Reasons for global change

The shift of exploration efforts and funds away from regions such as the U.S.A. or central Europe can be mainly attributed to two factors. First of all, these regions are considered 'over-explored' by many exploration companies, with new discoveries requiring disproportionally large financial, technical and scientific efforts.

Figure 2: Relative exploration expense in 1991 and 1997 according to region.

Figure 3: Exploration expenditure in million US$ according to region for 1991 and 1997.

Secondly, mineral exploration in 'highly developed' countries is increasingly obstructed by unfavourable public opinion resulting at least partly from an increased environmental awareness. There is a marked tendency in these highly developed countries to regard mining activity and hence exploration as a threat to high (environmental) living standards. The commonly expressed public opinion, that mining is highly undesirable, generally remains unquestioned by the increasing demand for processed natural mineral resources.

One could state that the hunter-gatherers have finally given way to (environmentally correct) traders and consumers. At the same time it becomes obvious that the global demand for mineral resources will continue to grow despite all first and second world attempts to reduce consumption and to optimise recycling techniques. Even the most optimistic scenario will have to include a constant or more probably a rising demand for mineral resources. The world's increasing population with its justified demands alone requires the discovery and development of new mineral deposits to replace exhausted ones and thus poses a serious challenge to future minerals supply.

Africa's new popularity

Of Africa's 47 mainland countries some 32 qualify as 'least developed nations' according to UN definitions. The continent holds 20 % of the earth's landmass with 670 million inhabitants. It is the world's largest gold producer and currently hosts some 45 % of the world's known gold reserves. Africa is geologically well endowed with Archean and Proterozoic terrains including an abundance of greenstone belts with their exceptionally high potential for gold deposits.

However, despite the recent significant increase it still attracts only 16,5 % of the world-wide exploration expenditure. Between 1985 and 1990, global political change with respect to the 'superpowers' and the abandoning of apartheid in South Africa resulted in a re-orientation of numerous African countries towards foreign investment and mineral exploration by international exploration companies.

Figure 4: Relative increase in exploration expenditure in each region betweeen 1991-97.

Figure 5: Ranking of exploration expenditure in 1991 according to region.

Figure 6: Ranking of exploration expenditure in 1997 according to region.

The opening process was not without difficulties due to a lack of experience with licensing and permitting procedures and in many cases the lack of fully established legal and fiscal rules in the minerals commodity sector. However, entrepreneurs, juniors and a large number of major exploration companies soon took the opportunity to claim ground in areas which in many cases had not been explored for more than 30 years, but with an impressive mining record from colonial times. More than 200 companies were conducting mineral exploration in sub-saharan Africa alone by 1996. Bilateral governmental aid projects helped to raise the information level of large prospective areas and to promote mineral exploration. Claiming known mineral occurrences faster than competitors was the most immediate and effective method of 'exploration' during the early years of this renewed exploration boom. However, the application of conceptual studies and modern multimethod mineral exploration projects followed shortly after.

The combination of high resolution aerogeophysics, remote sensing techniques and regional soil sampling programmes, processed by new GIS-systems has become almost a standard exploration procedure and has resulted in the identification of large numbers of highly prospective target areas.

Gold appears to be by far the most attractive commodity explored for in Africa with some 50 to 60 % of the expenditure being spent on gold exploration alone. Diamonds, platinum, zinc, copper, nickel, cobalt, bauxite, iron and manganese ores, and heavy mineral sands are amongst the other commodities that have attracted significant attention.

Low political risk, favourable investment conditions such as tax repatriation of dividends, corporate tax, free-carried interests, low royalty rates, and above all good geological indications are the main criteria to stimulate exploration in individual countries.

This has led to a tremendous exploration boom in Ghana and Tanzania, a considerable increase in exploration in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Mali, and increased levels of interest in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Senegal, Nigeria, Mauritania, the Central African Republic and Mozambique (Fig. 1).

To name an example, close to 100 million US $ have been spent during the last year on exploration in Tanzania alone. In the last few years this has resulted in the discovery of over 30 million new ounces of gold (measured and indicated).

Even traditional mining and exploration countries such as South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe have attracted a lot of renewed attention although these countries had been regarded for some time as relatively 'over-explored'. Yet, new exploration models and especially new ground mapping and remote sensing mapping techniques to identify and document regolith patterns have been developed in similarly arid terrains of Western Australia covered by sand or hard grounds.

Figure 7: Relative change in perecentage of global exploration expenditure within each region between 1991 and 1997.

These techniques are being successfully applied to African countries, turning some of them into viable exploration targets for foreign companies and thus attracting new exploration capital.

However, currently there is no similarly increased mining activity in Africa. This must be largely attributed to the fact that the exploration boom has started only some eight to ten years ago and the first newly discovered deposits are about to come into production shortly. African annual new production of gold, from outside of South Africa, stands at 560.000 oz per year between 1990 and 1996. Some 1.2 million oz/year of new production is expected for the year 2000.

Africa's new exploration geography and obstacles to the recent exploration boom

There remain severe obstacles to the exploration future of African countries since other areas of the world compete for the same global exploration capital. The lack of highly attractive fiscal regimes (when compared with Latin America), poor infrastructure, locally restrictive mineral policies and slow and corrupt government licensing agencies are severe threats to the newly emerging mining and exploration 'culture'. Currently, Latin America's top exploration countries are Chile and Peru where nearly all fiscal parameters are more attractive than in most African countries and have thus earned Latin America its current leading role in exploration terms.

The dramatic changes of mineral exploration in Africa described above have resulted in a new 'exploration geography' of the dark continent (Fig. 1). The African continent is now much more widely explored for its mineral wealth compared to any period prior to 1990.

Exploration funds from South African mining houses have been re-directed away from Southern Africa and towards West and East Africa. Virtually all international exploration companies have started to invest in the same regions and partly on Southern African terrain abandoned by South African mining companies. Two thirds of African countries are considered to be geologically highly prospective. However, continued civil war in Sudan and Angola and recent armed political conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, and Liberia inhibit exploration in some of these countries. It is uncertain how soon these regions might rejoin the group of countries that attract foreign investment for mineral exploration. Considering the strong interest that exists for future exploration in these war tormented countries almost two thirds of the African countries are currently explored or considered highly prospective. Ironically it appears that peace and political stability are considered prerequisites for mineral exploration and successful mining while the positive side-effects of mining, such as improved infrastructure, employment in the minerals sector, forex earnings, and an overall increase in GNP are amongst the best measures to prevent violent political conflict.

The role of ore deposit research and economic geology for mineral exploration

It goes without saying that the current increase in world-wide mineral exploration has also increased the number of known ore deposits as well as subeconomic but geologically significant mineral occurrences. This has resulted in a wealth of new geological information with respect to types and styles of mineralisation, alteration, and regional distribution patterns. New geophysical and geochemical methods as well as new exploration concepts have resulted, in many cases, from good communication and often from close co-operation between ore deposit research and the mineral exploration industry.

There is a high and growing demand for further practical ore deposit research which can be applied to day-to-day exploration. Thus it is important for the relevant scientific community to lend itself to this type of study and keep in mind the applicability of its research. It is surely not only to the benefit of the exploration companies to cooperate closely. The acquisition of new data and industrial funding of practical research will lead to a better understanding of the formation of ore deposits. This is especially relevant in the large and vastly underexplored regions of Africa. More opportunities than ever exist for the earth scientist to study recently discovered ore bodies to the benfit of science, industry, and African nations alike.

Back to Contents