- Yang Li1, John F. Slack2, and David L. Kelley3

- 1 Peking University

- 2 U.S. Geological Survey (Emeritus)

- 3 Chakana Copper Corp

Yellowstone Field Trip Summary (Co-sponsored by SGA and SEG)

Led by Jeff Hedenquist (University of Ottawa) and Stuart Simmons (University of Utah)

We recently had the privilege of participating in the SGA–SEG Yellowstone field trip, an exceptional learning experience led by two world experts in active geothermal systems and ancient epithermal environments, Jeffrey Hedenquist and Stuart Simmons. This trip brought together 25 participants representing 10 countries, with backgrounds from students to professionals in academia, industry, and government, creating a truly international and interdisciplinary atmosphere.

For many visitors, Yellowstone is mainly a holiday destination—a place to see a variety of wildlife, admire dynamic geysers, vivid colors, and dramatic landscapes, but often without an understanding of the geological processes generating them. This time, guided by two leading experts, the familiar sites of Yellowstone were transformed into a natural laboratory, where each feature becomes a window to understanding fluid flow, permeability evolution, mineral deposition, and the dynamics of magmatic-hydrothermal interactions, as expressed in the acid sulfate, alkaline chloride, and carbonate systems of the park.

9 August 2025, Upper Geyser Basin

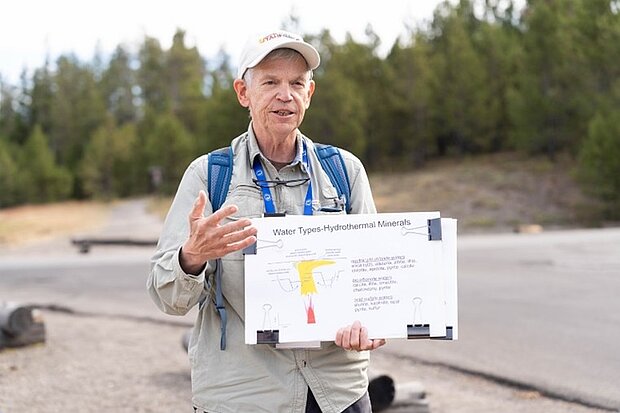

We began by learning from Stuart Simmons how water compositions control the minerals that form in hot springs. Water compositions in turn vary due to differences in temperature, pH, and fluid pathways (Fig. 1-4).

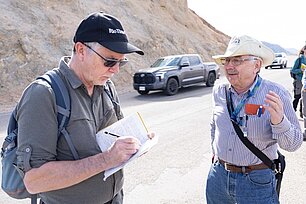

Mixed in with detailed descriptions of the geochemical processes throughout the park were some lighter moments and hands-on demonstrations (Fig. 5).

10 August 2025, Isa Lake and Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

Near Yellowstone Lake, we examined a roadside outcrop that beautifully exposes a sequence of volcanic eruption materials, hydrothermal breccias, and zones of intense alteration (Fig. 6). On the shore of Yellowstone Lake, we paused at another outcrop that records both eruptive and alteration processes shaping the caldera’s history. Blocks of eruption-derived breccia, hydrothermally altered sediments, and lake-reworked debris scatter the shoreline, offering a compact summary of Yellowstone’s past (Fig. 7).

One of the main attractions within the park is the steep, hydrothermally altered canyon walls of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, cut deeply by the Yellowstone River. This gorge highlights centuries of acid-sulfate alteration as reflected in the yellow, orange, and pink walls (Fig. 8, 9).

11 August 2025, Mammoth Hot Springs

Mammoth Hot Springs was the focus of the stops on our third day in the park. These immense fields of travertine deposits are shaped by constantly shifting hot spring waters, providing stark landscapes (Fig. 10-11).

12 August 2025, Lower Geyser Basin and Grand Teton

On our last day, we were fortunate to meet a Yellowstone park ranger who kindly paused to explain how the park has changed through the years. He described shifts in hydrothermal activity, long-term ecosystem recovery, and the challenges of balancing public access with preservation (Fig. 12).

Before heading back to Jackson, we were able to observe the effect that microbial material plays in the overall dynamics of Yellowstone. Microbial mats and floating patches of “foam” are composed of thermophilic bacteria that mark zones of active hydrothermal input (Fig. 13, 14).

Our SGA field trip offered an exceptional opportunity to observe Yellowstone’s hydrothermal architecture and dynamics in real time, as a modern analogue for understanding magmatic-hydrothermal systems and their expression in epithermal and porphyry environments. Across the basin we encountered classic upflow and outflow zones, sinter terraces, hydrothermal breccias, steaming ground, and alteration halos—features that closely parallel those preserved in many epithermal and porphyry districts.

The spatial arrangement of vents, mounds, and geyser basins reflected interplays among topography, permeability contrast, and structural control, illustrating how heat and fluids are channeled from deep magmatic sources to the surface.

For the industry participants, the trip provided an opportunity to observe features of modern hydrothermal systems and compare them to ancient systems targeted in their exploration programs. Of particular importance was understanding the contrasting alteration and geographic positioning between acid-sulfate upflow zones, boiling zones, and steam-heated zones.

Equally striking was the temporal dimension: episodic venting, overprinting alteration, and temperature-controlled sinter zonation revealed a distinctly pulsed and dynamic hydrothermal system, mirroring the transient behavior inferred from many ancient mineralizing environments. Yellowstone offered a rare modern analogue, showing directly how fluids mix, react, and redistribute heat and metals on short timescales. The trip also served as a valuable teaching refresher: witnessing active boiling, steam-heated alteration, and evolving fluid pathways gives new ways to communicate these processes to students.